Detroit’s City Council is currently considering the “Let’s Build More Housing, Detroit” zoning ordinance. The goal is to make it easier to build incremental density by allowing quadruplexes by-right where duplexes are currently allowed, changing side and setback requirements to make it legal to build smaller single-family homes on some of Detroit’s smaller vacant lots, and slightly decreasing parking minimums. These are very modest changes compared to other cities, like Minneapolis and Chicago, which are doing away with parking minimum requirements altogether. However, they have the potential to allow for greater walkability and more people-centered development in Detroit, which would make the benefits of said walkability more abundant and affordable for everyone in Detroit, not just those who can afford to live downtown.

While most residents at public meetings acknowledge that these changes are necessary to deal with the shortage of housing in our city, you hear some familiar complaints. How can we get rid of any parking, they complain, when our city doesn’t have transit?

Of course, transit does exist in the city of Detroit, but it is woefully underfunded. The Detroit area spends about a third of what the average American metro area does on transit per capita. Many of us take public transit in the city because, despite the narrative that Detroit is the Motor City, data has shown that 1 in 3 Detroiters don’t own a car. As transit riders in Detroit, we’re all too familiar with the experience of taking a bus somewhere only to find that our return bus seems to have vanished, or that it broke down, or service is low because of a driver shortage, mechanic shortage, or the other frequent issues that plague our underfunded system. These criticisms are valid, but the transit itself is only part of the story of why taking transit in Detroit can be unpleasant.

The proposed changes are supported by Transportation Riders United, the largest public transit advocacy group in SE Michigan, because transit riders greatly benefit from the incremental density that these types of zoning changes could bring, even without proposed service improvements. The proposed changes would be even more impactful for the rider’s experience in an underfunded system than they would be for a well-running system, because poor land use compounds the bad experience of a poor transit system, as is absolutely the case in Detroit.

Here are 7 reasons why density is important for public transit riders, even if service does not improve:

1. Low density spreads out amenities

Riding transit is not like driving. Transit, by its very nature, requires making stops, allowing people to get into the bus. Elderly riders may be shakily pushing individual dollar bills into the fare machine to pay for their ride. Sometimes a person in a wheelchair requires the bus driver to help strap them into a special harness. Since Detroit doesn’t have bus lanes, all of these stops are in addition to the traffic an individual car driver would experience. Increasing the distance of a trip increases the time of said trip far more than it would with a car. Additionally, all transit riders are also pedestrians (or sometimes cyclists). By spreading out businesses and residences with large “dead zones” of surface parking lots or requiring that large swaths of the city only allow for single-family or duplex housing, we increase the distances of both taking transit and walking. This makes doing everyday errands more of a burden for transit riders in a low-density environment.

One of the biggest challenges for Detroit residents is the availability of high-quality, affordable groceries within city limits. This is doubly so for Detroiters without cars, whose options are very limited to begin with. One popular option is the grocery store Joe Randazzo’s Fruit and Vegetable Market, which sells a large variety of produce at a very affordable price. It’s also transit-accessible, via the #7 7 Mile bus, the #5 Lafayette/Van Dyke bus, the #13 Conner bus and the #32 McNichols bus. With the exception of the #13 route, all of these buses drop the riders off to the South of the store, and many riders will enter from Antwerp St., which sits just off the Southwest corner of this aerial view of the store and its surroundings.

This design choice communicates whose time, safety, and convenience matter: there is no marked pedestrian route, no shelter from weather, and constant conflict with moving vehicles and delivery trucks. It adds friction, stress, and risk to an everyday task, particularly for seniors, people with disabilities, or anyone carrying bags. Although disability is often invoked as a reason for maintaining car-dependent infrastructure, there is no such thing as a “handicapped bus stop”, and many disabled people rely on public transit. They traverse the same long distance regardless and dodge traffic throughout.

2. A dense environment makes waiting for a bus more pleasant

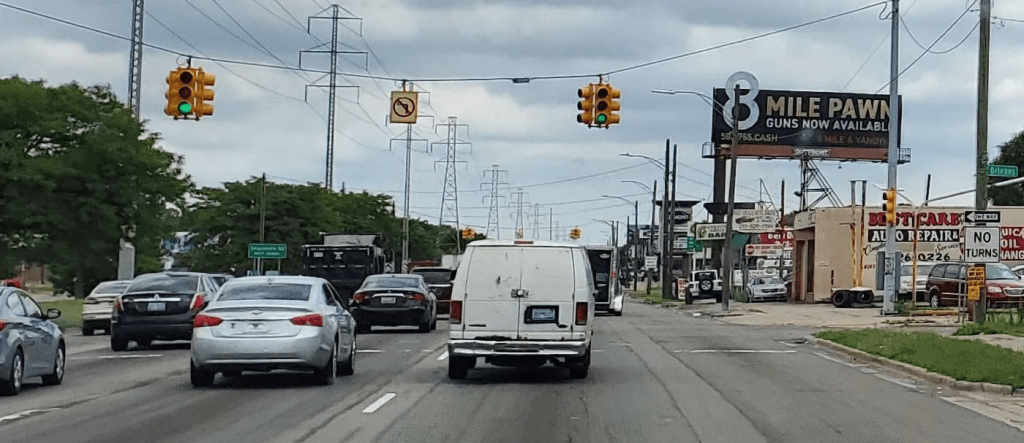

In addition to the discomfort and risk of walking three minutes through a large parking lot to get to one’s destination from a transit stop, simply waiting at a bus stop in an area that is designed for cars and a lack of density is less pleasant as well.

When you’re essentially trapped at a bus stop due to poor service or missed buses, the bus stop experience is important. It helps, of course, to have a bench or a shelter, but many DDOT stops lack either. In lieu of a shelter, however, an awning from a local small business, built at human scale and near the sidewalk instead of separated by a sea of asphalt, leverages density to create two types of infrastructure that are complementary when it rains. If you know your bus isn’t coming for 30 minutes or more (an unfortunately frequent experience dealing with DDOT), it would probably be worthwhile to grab a drink at a coffee shop or bar (not a problem if you won’t be driving!), providing comfort and refreshment to the bus riders while also making money in a local small business. You could browse a clothing store or thrift shop, perhaps even grab a meal if you won’t be home in time for lunch or dinner – again, something this author has unfortunately experienced with our unreliable system.

With our current land use, no comfort is forthcoming, no shelter provided–if it’s dry, you may sit on the ground–a common sight around bus stops in Detroit. There’s nothing for you to do but curse your bad luck.

To put it another way – would you rather miss a bus and be stuck for an hour on 7 Mile or in Midtown or Downtown?

3. Density makes it more likely to find more things on “your” bus route, making transfers less necessary

Now that you have a picture of what it looks like to be stranded at a bus stop in an area with car-dependent land use, think of what it’s worth for bus riders to avoid that fate. Making a simple transfer, which is no big deal in a city with more frequent transit, can add hours to your commute and increase the likelihood of being stranded – if your first bus is late, you miss the second bus, which even when the bus is running reliably, could be a once-an-hour bus, adding an hour to your commute. If that bus is missed, you’re looking at 2-3 hours of extra time to get where you’re going.

Now imagine Detroit has gone all-in on transit-oriented development, building up more density along transit corridors, requiring usage-driven parking instead of exception-driven parking based on Black Friday or sporting events. It’s now much more likely that your errand is on “your” bus route, making it less necessary to transfer buses to buy a simple hammer or pair of shoes. You might still get stranded, but you won’t get stranded twice.

4. Density makes it possible to do multiple errands in one place, saving bus riders an additional bus ride

This is a very similar benefit to the above, but worth mentioning on its own – instead of taking multiple buses to multiple errands, you may now be able to head to one place to get all of your needs. You can grab groceries, buy a gift for a family member, and maybe even go to the gym. This is possible in existing denser neighborhoods, like Rivertown, but if you grocery shop at Randazzo’s, chances are you won’t be able to do anything other than go to Randazzo’s without an additional trip. This also means another small business won’t benefit from the foot traffic of being near the primary destination.

5. Density makes it more likely that bus riders could just walk to something in their neighborhood without a bus ride

This is really the gold standard and the best-case scenario for bus riders in a system that needs serious improvement: not having to get on a bus at all and simply walking to one’s errand. This is why rents are high in Downtown and Midtown, because walkability improves quality of life even if you own a car.. Those high rents are simply an issue of supply and demand, because we have so few walkable neighborhoods that landlords in those areas can afford to charge a premium for that benefit.

We at Strong Towns don’t believe this should be a luxury that is only available to those who can afford to live in one of the handful of existing dense neighborhoods. We want the advantages of walkability to be available to as many residents as possible, which requires changing our laws to enable the density that makes that possible. Which brings us to our next point…

6. More density means cheaper housing over time near frequent transit corridors

Because housing in walkable areas is in low supply and high demand, creating more walkable neighborhoods in the city will slow the pace of increasing rents in the city. Additionally, easing some mandatory parking minimums and making it easier to build on vacant lots by changing side and setback requirements is an easy way to lower the cost to develop, instead of increasing the generous subsidies that our current approach relies on. Why should we continue to give them taxpayer dollars to mitigate the cost of submitting variances and rezoning paperwork when we can streamline that process and get more bang for our buck?

7. More density means more people who care about transit

This is perhaps the most impactful, though most abstract, benefit of all: if we make it less unpleasant to be a bus rider, even without service improvements, more people will take the bus, building a larger constituency of citizens who care about transit and may advocate for those sorely needed service improvements.

While this city has some incredibly dedicated transit advocates, bus riders as a constituency don’t have the power they need. When you have to transfer between buses for literally 2-3 hours to run a simple errand, that time adds up. Free time that could be spent in city council meetings or mayoral forums is a privilege that most bus riders simply don’t have. There’s a reason our city’s most active public transit advocate is the world’s most selfless taxi driver. Poor bus service robs Detroiters of access to good-paying jobs, and the reliability they need to get to them, and the system is so broken that it is generally viewed as a last resort. Listen to any elected official or even some well-meaning allies talk about transit, and you’ll see they often think of it as welfare for the poor and something to “graduate” from at the moment you can afford your own car.

But the benefits of transit-riding could be available to many more people, and not just the most vulnerable. Riding transit saves thousands of dollars a year in car payments, gasoline or electricity, Detroit’s famously high auto insurance, maintenance and repairs. Riding public transit often results in more walking, which can be a public health boon. It cuts down on the greenhouse gases associated with individual car use, as well as the air pollution that makes Detroit the worst city for asthma sufferers in the nation.

If we make the experience of riding a bus more pleasant via better land use, where riders aren’t sitting on the dirty ground next to a loud, dusty stroad for an hour or two, these intrinsic values of public transportation will become more widespread and appealing to a broader diversity of residents. More people would have the free time or money to dedicate to better transit in the Motor City, pressuring our elected officials in Detroit and Lansing to fund our transit system and improve it. And those riders who are vulnerable will finally be able to benefit from a dignified transit system in Detroit.

The complaint that there is “no transit in Detroit” should not be a reason to reject much-needed zoning changes. Instead, we should ask, “What are the public transit possibilities that these changes could unlock?” We should aim to build a city where transit is an amenity of our neighborhoods, not a last resort.

Leave a comment